The Science

While some applications of HGE are benign and hold great potential for preventing disease and alleviating human suffering, other applications could open the door to a human future more horrific than our worst nightmares.

Two very different applications of genetic engineering must be distinguished. One application changes the genes in cells in your body other than your egg and sperm cells. Such changes are not passed to any children you may have. Applications of this sort are currently in clinical trials and are generally considered socially acceptable. The technical term for this application is "somatic" genetic engineering (after the Greek "soma" for "body").

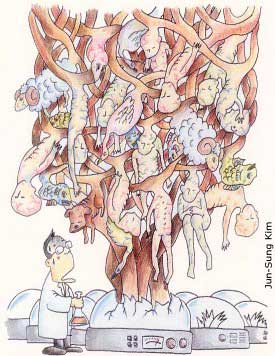

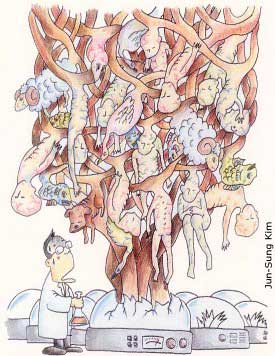

The other application of genetic engineering changes the genes in eggs, sperm, or very early embryos. This affects not only any children you might have, but also all succeeding generations. It opens the door to the reconfiguration of the human species. The technical term for this application is "germline" genetic engineering (because eggs and sperm are the "germinal" or "germline" cells).

Many advocates of germline engineering say it is needed to allow couples to avoid passing on genetic diseases such as cystic fibrosis or sickle cell anemia. This is simply not true. Far less consequential methods (such as pre-natal and pre-implantation screening) already exist to accomplish this same goal. Germline manipulation is necessary only if you wish to "enhance" your children with genes they wouldn't be able to get from you or your partner.

The History

The ability to directly manipulate plant and animal genes was developed during the late 1970's. Proposals to begin human gene manipulation were put forth in the early 1980's and aroused much controversy. A small number of researchers argued in favor of germline manipulation, but the majority of scientists and others opposed it. In 1983, a letter signed by 53 religious leaders declared that genetic engineering of the human germline "represents a fundamental threat to the preservation of the human species as we know it, and should be opposed with the same courage and conviction as we now oppose the threat of nuclear extinction."

In 1985, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) approved somatic gene therapy trials, but said that it would not accept proposals for germline manipulation "at present." That ambiguous decision did little to discourage advocates of germline engineering, who knew that somatic experiments were the critical first step toward HGE experiments. Following the first approved clinical attempts at somatic gene therapy in 1990, advocates of germline engineering began writing advocacy pieces in medical, ethical, legal and other journals to build broader support.

By the mid- and late-1990s, the progress of the federally funded Human Genome Project in locating all 80,000-plus human genes fueled speculation about eventual applications, including germline engineering. In 1996, scientists cloned the first genetic duplicate of an adult mammal (the sheep "Dolly"). In 1999, researchers mastered the techniques for disassembling human embryos and keeping embryonic cells alive in laboratory cultures. These developments made it possible, for the first time, to imagine a procedure whereby the human germline could be engineered in a commercially practicable manner.

HGE advocates were further encouraged by the social, cultural and political conditions of the late 1990s -- a period characterized by technological enthusiasm, distrust of government regulation, the spread of consumerist/ competitive/ libertarian values, and the perceived weakened ability of national governments to enforce laws and treaties, as a result of globalization.

In March 1998, Gregory Stock, director of the Program on Medicine, Technology and Society at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), organized a symposium on "Engineering the Human Germline." It was attended by nearly 1,000 people and received front-page coverage in The New York Times and The Washington Post. All the speakers were avid proponents of germline engineering.

Four months later, one of the symposium's key participants, HGE pioneer W. French Anderson, submitted a draft proposal to the NIH to begin somatic gene transfer experiments on human fetuses. He acknowledged that this procedure would have a "relatively high" potential for "inadvertent gene transfer to the germline." Anderson's proposal was widely acknowledged to be strategically crafted so that approval could be construed as acceptance of germline modification, at least in some circumstances. Anderson hopes to receive permission to begin clinical trials by 2003.

The New Ideology

Advocacy of germline engineering and techno-eugenics (i.e., technologically enabled human genetic manipulation and selection) is an integral element of a newly emerging socio-political ideology.

This ideology is gaining acceptance among scientific, high-tech, media and policy elites. A key foundational text is the book Remaking Eden: How Cloning and Beyond Will Change the Human Family, by Princeton University molecular biologist Lee Silver. Silver looks forward to a future in which the health, appearance, personality, cognitive ability, sensory capacity and the lifespan of our children all become artifacts of genetic manipulation. Silver acknowledges that financial constraints will limit their widespread adoption, so that over time society will segregate into the "GenRich" and the "Naturals."

In Silver's vision of the future:

"The GenRich -- who account for ten percent of the American population -- all carry synthetic genes. All aspects of the economy, the media, the entertainment industry, and the knowledge industry are controlled by members of the GenRich class ...

Naturals work as low-paid service providers or as laborers. [Eventually] the GenRich class and the Natural class will become entirely separate species with no ability to crossbreed, and with as much romantic interest in each other as a current human would have for a chimpanzee.

Many think that it is inherently unfair for some people to have access to technologies that can provide advantages while others, less well-off, are forced to depend on chance alone, [but] American society adheres to the principle that personal liberty and personal fortune are the primary determinants of what individuals are allowed and able to do.

Indeed, in a society that values individual freedom above all else, it is hard to find any legitimate basis for restricting the use of repro-genetics. I will argue [that] the use of reprogenetic technologies is inevitable. [W]hether we like it or not, the global marketplace will reign supreme."

The Environment

HGE enthusiasts typically anticipate a future in which genetic technology permeates, transforms and reconfigures all sectors of the natural world -- plants, animals, humans and ecosystems. Many look forward to what they call the "Singularity" -- that point in the next few decades when any distinction between the natural and the technological has been completely dissolved. Many couple their enthusiasm for genetic engineering with an explicit disparagement of environmentalist values. Nobel Laureate James Watson, for example, has complained that "ever since we achieved a breakthrough in the area of recombinant DNA in 1973, left-wing nuts and environmental kooks have been screaming that we will create some kind of Frankenstein bug or Andromeda strain that will destroy us all."

Gregory Stock has stated: "Even if half the world's species were lost, enormous diversity would still remain. When those in the distant future look back on this period of history, they will likely see it not as the era when the natural environment was impoverished, but as the age when a plethora of new forms -- some biological, some technological, some a combination of the two -- burst onto the scene. We best serve ourselves, as well as future generations, by focusing on the short-term consequences of our actions rather than our vague notions about the needs of the distant future."

It is difficult to see how a society that accepts the techno-eugenic re-engineering of the human species will maintain any sense of humility, reverence and respect regarding the rest of the natural world.

Promoting the 'Post-Human' Future

Supporters of human germline engineering and cloning have established institutes to spread their vision. In addition to Stock's program at UCLA, the Los Angeles-based Extropy Institute holds workshops on how to organize politically to advance the "post-human" agenda, including sessions on how to talk to the press and public about human genetic modification in ways that build support and diffuse opposition. In 1999, the Maryland-based Human Biodiversity Institute presented a seminar on the prospects for genetically modified humans at a Hudson Institute retreat attended by former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

Meanwhile, the biotech industry is actively developing the technologies that would make it possible to offer human germline engineering on a commercial basis. This work is almost completely unregulated. Geron Corporation of Menlo Park, California holds patents on human embryo manipulation and cloning techniques. Advanced Cell Technologies of Worcester, Massachusetts, announced in 1999 that it had created a human/bovine embryo by implanting the nucleus of a human cell into the egg of a cow. No laws exist that would have prevented this trans-species embryo from being implanted in a woman's uterus in an attempt to bring a baby to term. Such a child would have contained a small but significant proportion of cow genes.

Chromos Molecular Systems, Inc., in British Columbia, is developing artificial human chromosomes that would enable the engineering of multiple complex traits. People whose germlines were engineered with artificial chromosomes, and who wanted to pass complete sets of these to their children intact, would only be able to mate with others carrying the same artificial chromosomes. This condition, called "reproductive isolation," is the primary criteria that biologists use to classify a population as a separate species.

Where is the Opposition?

Given the enormity of what is at stake and the fact that advocates of the new techno-eugenics are hardly coy about their intentions, it is remarkable that organized opposition has been all but absent. Why is this?

One reason is that the most critical technologies have been developed only within the last three years or so -- there simply hasn't been time for people to fully understand their implications and respond. Further, the prospect of re-designing the human species is beyond anything that humanity has ever before had to confront. People have trouble taking this seriously -- it seems fantastical and beyond the limits of what anyone would actually do or that society would allow.

In addition, attitudes concerning human genetic engineering don't fit neatly along the familiar ideological axes of right/left or conservative/liberal. The additional axis of libertarian/communitarian attitudes is needed to fully categorize currently contending socio-politico commitments. The libertarian right and libertarian left tend to consider human genetic modification as a property right or as an individual right, respectively. By contrast, the communitarian right and communitarian left tend to be strongly opposed -- the former typically for reasons grounded in religious beliefs and the latter out of concern for human dignity, social equity and solidarity.

Finally, although people sense that the new genetic technologies are likely to introduce profound social and political challenges, they also associate these technologies with the promise of miracle cures. Before any sentiment in favor of banning certain uses of genetic technology can take root, people will have to understand that this would not foreclose means of preventing or curing genetic diseases.

What Is to be Done?

The core policies that humanity will need to adopt are straightforward: we will need global bans on altering the genes we pass to our children and on creating human clones. We'll also need effective, accountable systems for regulating those HGE technologies (such as somatic genetic manipulation) that have desirable applications but could be dangerously abused.

Many countries, including France, Germany and India, already have banned both germline engineering and cloning. The Council of Europe is working to have these banned in all 41 of its member countries. The United Nations and UNESCO have called for a global ban on human cloning and a World Health Organization study has called for a global ban on germline engineering.

The base of any effective global movement to bring the new human genetic technologies under societal control will, as always, be strong activist civil society organizations. Among the most important of these are the environmental and Green organizations. In 1999, Friends of the Earth President Brent Blackwelder and Physicians for Social Responsibility Executive Director Robert Musil circulated a statement that declared:

"We believe that certain activities in the area of genetics and cloning should be prohibited because they violate basic environmental and ethical principles. We believe that germline manipulations, for their ability to change whole generations, not just individuals, go far beyond the boundaries of human scientific and ethical understanding and are too dangerous for human civilization to pursue. Being a product of scientific design and manipulation as opposed to natural chance will fundamentally change the place of the individual in society and would profoundly alter the relationship of human beings to the natural world."

In February 2000, nearly 250 concerned leaders, including environmentalists Bill McKibben, Amory Lovins, Terry Tempest Williams, Gary Snyder and Mark Dowie, signed an open letter warning that the prospect of human germline engineering "represents a point of decision -- one that ranks among the most consequential that humanity will ever make. We should acknowledge that human germline engineering is an unneeded technology that poses horrific risks, and adopt policies to ban it."

The next few years will be critical. Advocates of the techno-eugenic future are racing to create designer babies and human clones before people realize what is happening and what is at stake. They believe that once humanity is presented with such fait accompli, resistance will crumble and the new epoch will have been launched. It is imperative that those who value the beauty, vitality and wonder of the natural world begin organizing now to ensure that human beings do not become technological artifacts.

Richard Hayes is the Executive Director of The Center for Genetics and Society